Nowadays, memes are everywhere. They reflect internet culture and its participants, and it's pretty safe to say that every one of us has encountered them. The historical sciences, however, have hardly discovered the possibilities offered by memes.

A Short History of Memes

It's debatable what the first meme was, and they might be even older than the internet. Famous pre-internet memes included “Kilroy was here.” During World War II, American soldiers often painted a humanoid face with a long nose on walls. The sentence “Kilroy was here” frequently accompanied this face. The reach of the “Kilroy was here”-meme was limited to the places where those who knew the meme could go.

Today, memes are available to everyone with internet access. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, memes began to rise. Back then, many memes appeared in the form of so called “single-serving sites” – websites with only one use. The most famous of those single-serving sites might be the “Hamsterdance” [1], created by art student Deidre LaCarte in 1998. It shows a bunch of dancing hamsters while playing an accelerated version of the "Whistle Stop" from the Disney movie "Robin Hood”.

In the same year, the first tool for creating memes, the “Parody Motivator Generator”, was put online. It was a reaction to the success of the so-called Demotivational Posters from the 1970s and 1980s. Initially, only those who knew graphic design and programming could make memes. It often took hours to create a meme, as seen in ASCII art. It uses letters and symbols from the American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII), a character encoding standard, to create pictures. With the rise of meme generators more people could make their own memes. The increasing accessibility of memes has led to a rise in their popularity. Soon memes were not single websites anymore but distributed on new platforms, like Something Awful [2.] in 1999. Memes were no longer found on isolated pages on the Internet but were bundled together on meme websites.

But what are memes, exactly?

The word "meme" was coined in 1976 by British evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins in his book "The Selfish Gene". Initially, he derived the word from the Greek mimema (imitated) and changed it to rhyme with “Genes.” Dawkins argues that a cultural DNA exists, which behaves like genes according to the rules of evolution. Why the Internet eventually adopted the term is unclear. Dawkins himself later described the takeover as "a hijacking of the original idea." [3.] The parallels between Dawkins’s concept and todays internet memes are apparent. An internet meme must be easily understandable and reproducible. For a meme to exist successfully, it must catch on and be shared as often as possible. A meme is a medium to communicate, but memes, in general, are more of a genre ranging from videos to the “classical” macro pictures. In 2013, Israeli internet researcher Limor Shifman published the article "Memes in Digital Culture", the standard scientific work on internet memes. She defines memes as:

“(a) a group of digital items sharing common characteristics of content, form, or stance, which (b) were created with awareness of each other, and (c) were circulated, imitated, and transformed via the internet by many users.“

A meme goes through three different stages. First, so-called spreadable media exists, like a movie trailer. Those are often shared in an unaltered form. As soon as people start interacting with the medium and change it, it becomes an emergent meme. Due to excessive further interaction, it spreads and finally becomes an internet meme. According to Shifman, the central factors behind memes are the principles of remix and imitation. Even the spreadable medium has its meaning. By alteration and interaction, a new layer and a new connotation is added. The users are creating their own language – through intertextuality.

The crucial point is that memes – quite similar to Dawkin's concept – compete with each other. Anyone can create, upload, and distribute a meme. They are an expression of a “do-it-yourself”-culture which is as diverse as the opinions of those who participate. At the same time, memes have to be entirely self-explanatory to those familiar with their language. The complexity of memes goes so far that in 2008 the website "Know your Meme" [4.] was founded, a database that explains the origins of various memes. But still, memes evolved to be the internet’s lingua franca.

“How people feel about this past” - Historical Memes

History memes are not fundamentally different way from other memes. What makes them special is their content: They refer to historical circumstances, persons, use historical imagery – or combine those elements. This way, they allow individuals to express their views on history, which may differ from the existing historical narratives. Social networks also offer the opportunity to engage with and discuss these altered views. Through these interactions, memes can also initiate further interest. However, history memes are not meant to educate; they are made for entertaining. There is no level on which the meme’s meaning is explained. If they require too much historical knowledge, it’s safe to assume that most users will not understand them, and the meme is unsuccessful.

On the other hand, memes don't have to appeal to everyone as they are usually created to circulate within a specialized group. Those groups typically function as self-serving systems - they simply make the content they want. But while movies, computer games and books sometimes have costume designers, developers, and an editorial team, creating memes is a one-person-business. Therefore, many memes cater to historical prejudices and misconceptions that exist in public opinion. Only the users interacting with memes can act as a supervisory body and call out those mistakes in the comments. But this function is rarely used.

History memes have no claim to historicity. The media used to create a meme does not necessarily have to be from the period in question. Many memes use modern macro imagery to represent historical narratives. That might also be a source of inaccuracy, as contributors often use the wrong pictures. This adds to the fact that memes are not about historical accuracy, but about their own message. They do not tell us something about history – but the public view of history. Mykola Makhortykh argues in his article about World War II memes:

„Quick, accessible, entertaining and sometimes vulgar, historical internet memes tell us mainly not about the past, but about how people feel about this past.“(Makhortykh, S. 88)

Medieval Memes

This holds true for memes about different eras, too. Medieval memes have little to do with the "real" Middle Ages. Instead, we often find many modern medieval tropes: knights, flowery language, weapons. And a focus on Europe, as well as jokes about the Black Death and the allegedly high mortality rates as the focus of the memes. They romanticize the medieval while also making fun of it. In his essay, "Dreaming of the Middle Ages,” Umberto Eco talks about the current treatment of the Middle Ages in pop culture: “The Middle Ages preserved in its way the heritage of the past but not through hibernation, rather through a constant retranslation and reuse.” In our modern media landscape, it seems that the medieval itself has become a

meme.

Images dominate our modern media. With an abundance of pictures and prints, the Middle Ages gladly meet this demand for visual communication. This is best seen in the spread of medieval art memes. Here, medieval imagery (and often early modern imagery) becomes the meme’s main source. Most of the time however, it is enough for the images to give the impression of being a medieval artefact. Sometimes they are used to reflect modern society, and other times they are playing with history.

As early as in 2002, two students from the Cologne University of the Arts created a free tool on the Internet for memes based on the Bayeux Tapestry (late 11th century); a 67-meter-long carpet embroidered with central scenes about the Battle of Hastings. Individual figures from the tapestry can be placed in new contexts. With the Historic Tale Construction Kit [5.], the creators may add text. These so-called "Bayeux Tapestry Memes" form a widespread genre of their own within this category.

The recreation of "medieval" art is not limited to a pictorial level. In recent years, "medieval" covers of modern songs have become increasingly popular. These types of memes are known as "Medieval Style Cover,” "Bardcore," or "Tavernwave.” Although the genre has been around since the late 2000s, it has gained inflationary popularity since April 2020. According to knowyourmeme.com [6.], one of the first representatives of this genre was the video "Medieval Music - 'Hardcore' Party Mix.” [7.] It was uploaded to YouTube by Paul Vakna in 2009. Since then, YouTube Channels like “the_miracle_aligner” or “Hildegard von Blingin'” are regularly uploading new videos.

New possibilities for Public History?

The imagined “Otherness” of the Middle Ages still fascinates us today and allows the Middle Ages to be reinvented or appropriated by our contemporary culture. These changes are in the hands of the public, which also gives historians new opportunities. In their article about medieval memes, Maggie M. Williams and Lauren C. Razzore conclude:

“Medieval memes allow the general public to share knowledge and ideas, and at the same time, they offer trained professional historians the opportunity to communicate with wider audiences. Through humour, they encourage creative and intellectual collaborations, and make the Middle Ages comfortable, familiar and interesting to modern audiences” (Razzor/Williams, S. 331.)

Not only medieval memes, but historical memes in general could serve as a new form of communication with the public for open-minded researchers. Currently, the only historically trained meme creators are primarily students. Through sharing memes, they communicate with each other as well as non-professional friends and evoke interest for their field of studies. By doing that, historical memes could acquire real educational value.

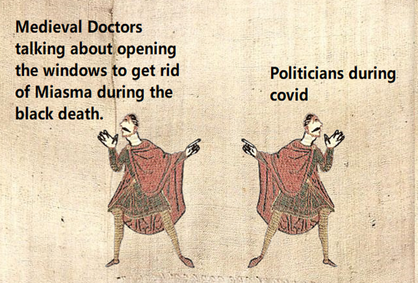

They also present real research opportunities for public historians. Historical memes provide a unique glimpse into the public’s understanding of history itself. And creators process their own present through history memes, too (as seen in the meme about Covid above). History memes build a bridge between the past and pop culture. As research objects, they can be used to examine popular historical thinking. Researchers should always approach history memes critically, however. A meme is not a medium that is able to do justice to the complexity of history. Instead, they’re mostly rather simplistic, non-serious forms of entertainment created by people who consume them. Memes are fun – and as historians, we can also have fun with them.

Written by Julia Göke

Links (external websites):

[1.] https://www.webhamster.com/ (24.10.2022)

[2.] https://www.somethingawful.com/ (24.10.2022)

[3.] https://youtu.be/T5DOiZ8Y3bs (24.10.2022)

[4.] https://knowyourmeme.com/ (24.10.2022)

[5.] https://htck.github.io/bayeux/#!/ (24.10.2022)

[6.] https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/medieval-style-cover (24.10.2022)

[7.] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xaRNvJLKP1E (24.10.2022)

Further Reading:

Dawkins, Richard: The Selfish Gene, Oxford/New York 1989.

Eco, Umberto: Dreaming of the Middle Ages, in: Travels in Hyperreality, by Umberto Eco, New York 1986, pp. 61–72.

Fugelso, Karl: Medievalism from Here, in: Studies in Medievalism 17 (2009), pp. 88-91.

Göke, Julia Marie: Mittelalterbilder in sogenannten „Memes“ auf sozialen Netzwerken, in: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bsz:352-2-1rgo878k9euip5, Konstanz 2020.

Makhortykh, Mykola: Everything for the Lulz. Historical Memes and World War II Memory on Lurkomor’e, in: Digital Icons. Studies in Russian, Eurasian and Central European New Media 13 (2015), pp. 63-90.

Shifman, Limor: Memes in Digital Culture, Cambridge, Mass. / London 2014.

Wiggins, Bradley E.: The Discursive Power of Memes in Digital Culture. Ideology, Semiotics, and Intertextuality, New York 2020.

Infospalte

Aktuelle Kategorie:

… auch interessant:

Stuttgart erinnert an den Nationalsozialismus Teil 1/2

Verwandte Themen:

Geschichtslernen digital

Folge uns auf Twitter:

Kommentar schreiben